La ricca e varia collezione sudarabica del Museo Nazionale d’Arte Orientale ‘Giuseppe Tucci’ comprende iscrizioni, sculture, rilievi, elementi architettonici, oggetti in bronzo e monete. Questi oggetti rispecchiano l’originalità della produzione artistica dello Yemen pre-islamico. La produzione artistica degli antichi regni sudarabici consiste da un lato di oggetti – come statue, tavole offertorie (fig. 4), altari, bruciaprofumi troni, lastre e iscrizioni votive – connesse con il culto, dall’altro di opere connesse con il mondo dei morti come stele (fig. 5) e statue funerarie.

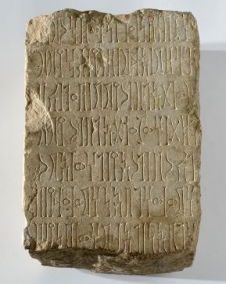

Le iscrizioni commemorative o dedicatorie (fig. 6) sono una fonte diretta per la documentazione delle divinità del pantheon ufficiale, comune al tutto il popolo sudarabico, che includeva anche divinità locali, venerate in particolari contesti o tribù.

Le stele votive sono caratterizzate da un pannello centrale dove è incisa l’iscrizione, contornata da una cornice scolpita con false finestre e dentelli. Negli esemplari più elaborati compaiono anche teste di stambecco o tori, stambecchi accosciati, oltre a tori alati e sfingi ai lati di una pianta sacra di derivazione mesopotamica e persiana.

Statuette a tutto tondo, note come le antenate (fig. 7) appartengono alla fase più antica dell’arte sudarabica (7-6 secolo a.C.). Queste sculture in calcare o pietra tenera furono in gran parte portate alla luce nell’area del Jawf e spesso in contesti funerari. Potrebbero raffigurare i defunti seduti, forse a banchetto, secondo un modello iconografico attestato in Siria all’inizio del I millennio a.C.

I corpi massicci, i seggi cubici, la rigida fissità, e la mancanza di proporzioni tra il busto e le gambe, sono elementi tipici della produzione locale di queste statuette.

Ritratti simbolici e stele funerarie erano collocate nelle tombe presso il corpo del defunto insieme ad oggetti di uso quotidiano (ceramiche, gioielli, armi ecc). Le stele funerarie prodotte tra il III secolo a.C. ed il III secolo d.C rappresentano una simbolica e schematica raffigurazione del defunto: alcune sono aniconiche, altre raffigurano solo gli occhi circolari o romboidali, o il volto del defunto inciso o a rilievo o una testa di toro accompagnati da una breve iscrizione

Un altro tipo di stele funeraria databile tra il II e il III secolo presenta scene narrative o di vita quotidiana, raffigurate in una serie di registri, all’interno di una cornice con elementi floreali (fig. 8).

Dopo la conquista dell’impero achemenide da parte di Alessandro Magno, anche l’arte sudarabica subì molte trasformazioni. Molte opere furono importate, ma altre furono prodotte da artigiani locali sotto l’influenza dell’arte ellenistica (fig. 9).

The South-Arabian Collection of the Museo Nazionale d’Arte Orientale

The rich and varied South Arabian collection of the Museo Nazionale d’Arte Orientale ‘Giuseppe Tucci’ includes inscription, sculptures, architectonic elements, bronze objects and coins. These items mirror the originality of the artistic production of the pre-islamic Yemen.

The artistic production of the ancient South Arabian kingdoms consists on one side of objects – like statues, libation tables (fig. 4), altars, incense burners, thrones, slabs and votive inscriptions – connected with the cult, on the other side of works of art connected with the world of the dead like funerary steles (fig. 5) and statues.

Commemorative and dedicatory inscriptions (fig. 6) are a direct source for the documentation for the deities, of the official pantheon, common to all South Arabian people, which included also local gods, venerate in particular contexts or tribe.

Statuette in the round, known as the “Ancestors” (fig. 7), belong to the most ancient phase of South Arabian art (7th-6th century BCE). These sculpture in limestone or sandstone were brought to light in the Jawf area and often in funerary contexts. They could represent the deceased seated, maybe at a banquet, following an iconography model present in Syria, during the 1st Millennium BCE.

The massive bodies, the square seats, the structural immobility and the disproportioned torso and legs, are typical elements for the production of these statuettes.

Symbolic portraits and funerary stelae were placed in tombs near to the body of the deceased, with objects of every days use (pottery, jewelry, weapons, etc.). The funerary stelae produced between the 3rd century BCE and the 3rd century, present a symbolic and schematic depiction of the deceased:

Some of these are aniconic, others have only the stylized circular or rhomboidal eyes, or the face of the deceased carved or in relief or a bull’s head, all with a short inscription.

An another type of funerary stelae datable between the 2nd and the 3rd century shows narrative scenes or of everyday life, depicted in a series of registers into a frame with flowers elements (fig. 8).

After the conquest of Achaemenid Empire by Alexander the Great also the South Arabian art underwent several transformations. May works of art were imported, but others were executed by local craftsmen, under Hellenistic influence (fig. 9).