The origins and history of the collections

From the Royal National Prehistoric Ethnographic Museum (1875) to the Museum of Civilizations (2016)

The Royal National Prehistoric Ethnographic Museum of Rome, originally housed in the building of the former Roman College, was founded in 1875 by archaeologist Luigi Pigorini. These were the years immediately following the unification of Italian territories as a new kingdom, and in keeping with the intentions of its founder, the aim of the institution was to serve as a national repository for the documentation and study of the prehistoric cultures of Italy, but also of Europe and the larger world, and of non-European ethnographic cultures in general, all of which considered as “primitive.”

The Roman College, built by the Order of Jesuits, had since the 1600s housed the collection of antiquities and curiosities assembled by Father Athanasius Kircher, and it was this “Kircherian museum” that Pigorini assumed as the nucleus of the Royal Museum. The first collections of an ethnographic nature had thus been assembled between 1635 and 1680 by Father Kircher himself, from Capuchin missions in the Congo and Angola and Jesuit missions in China, Brazil and Canada. Along with the Kircherian core there were also exotic “curiosities” brought from the New World and preserved in the most important collections of 18th-century Italy – such as those of Cardinal Flavio Chigi Senior and Cardinal Stefano Borgia – as well as others brought from around the world by merchants, missionaries and travelers, up to the late 19th century and continuing after the museum’s founding.

The museum developed its ethnographic collections further through purchases and gifts. The House of Savoy, for example, donated numerous objects, including musical instruments from Hindustan and women’s ornaments from the nomadic cultures of North Africa. Pigorini also worked out personal agreements, and others through the Ministry of Education, with the commanders of transoceanic scientific expeditions organized by the Ministry of the Navy, seeking objects and photographs from the lands explored. In addition the Italian Geographical Society, headquartered on the main floor of the Roman College, conducted its own expeditions, and from these turned over objects of ethnographic interest to the Royal Museum. Particularly fruitful in this regard were the expeditions of Giacomo Bove in Tierra del Fuego, and Romolo Gessi in the regions of East Africa.

The first layout of the Royal Museum derived from worldviews that placed human civilizations on an imaginary evolutionary scale, also of service in colonial narratives and practices. Among the non-Europeans, the Asian continent was at the apex, as seen in the first rooms of the exhibition itinerary. The visitor would then continue their visit through the rooms devoted to the Americas, beginning with the north and continuing south, then the rooms devoted to the Oceanian collections, and finally those focusing on Africa.

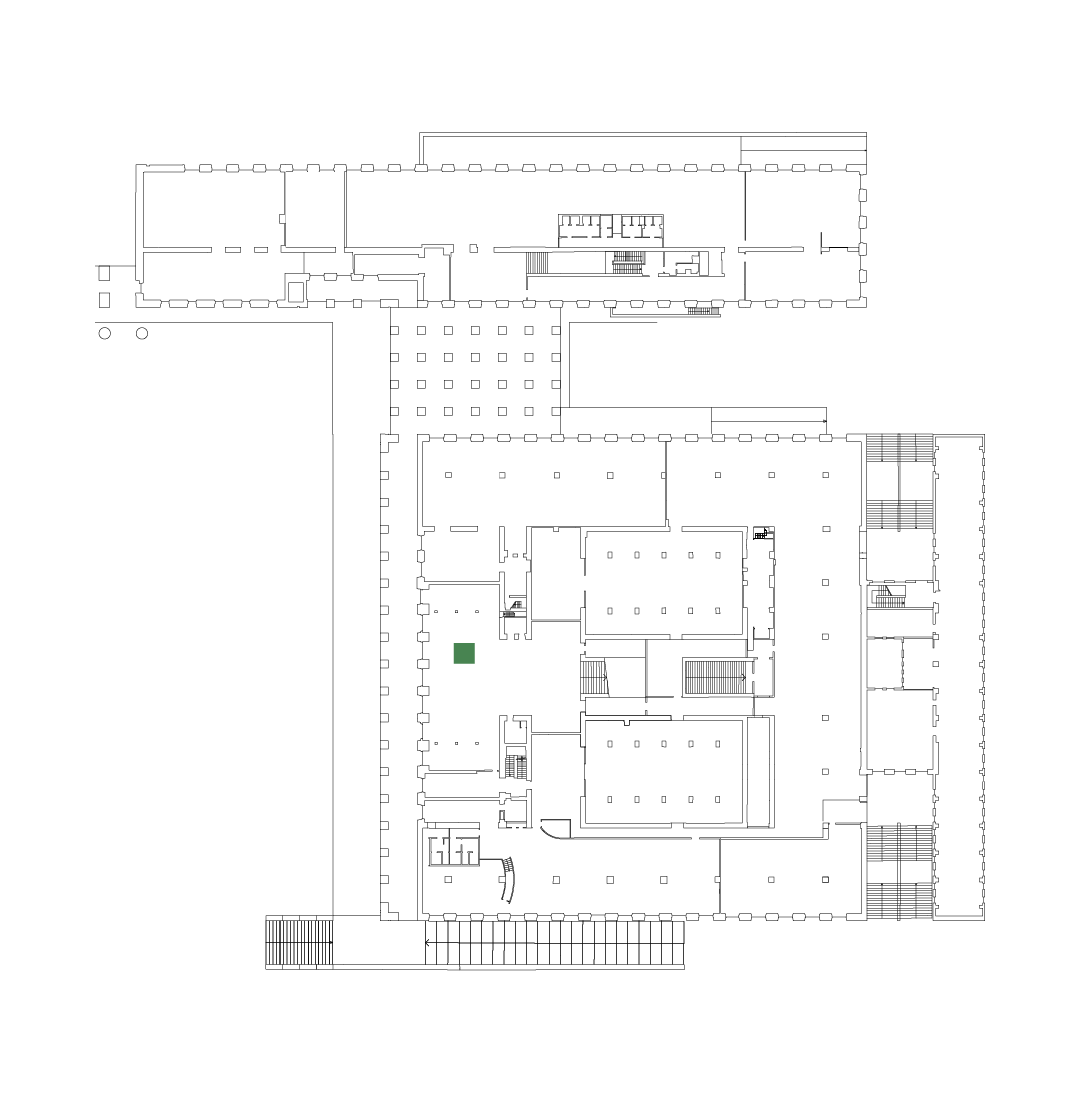

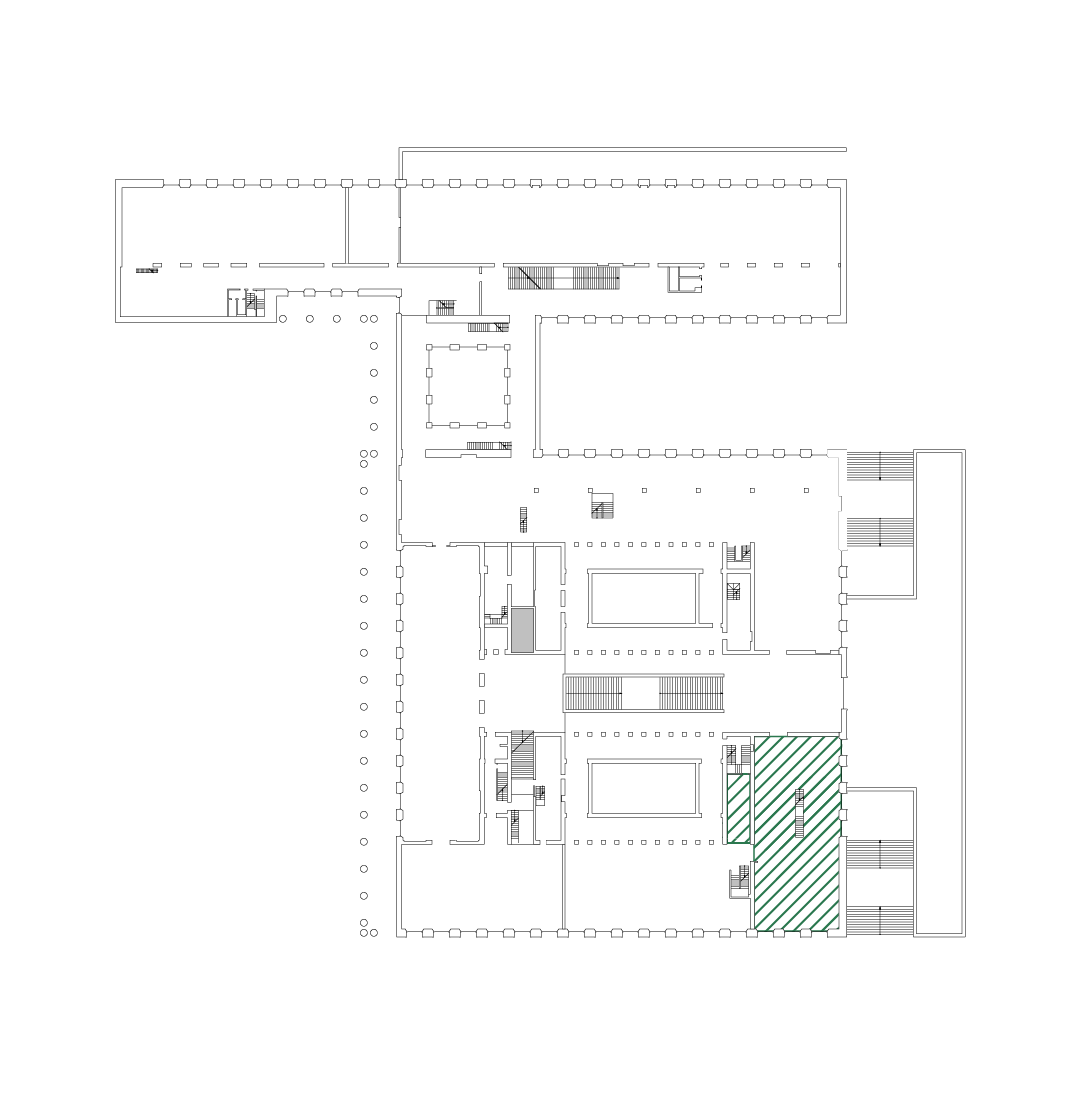

Roughly a century later, and renamed the National Prehistoric Ethnographic Museum following the founding of the Italian republic, the museum left the premises of the Roman College to the new Ministry of Cultural and Environmental Heritage and transferred entirely to the EUR Palace of Sciences. At this time, around 1975-77, the museum still retained its original organization in two sectors: Prehistory and Extra-European Ethnography.

However by now the academic device of comparison between prehistoric societies and societies of ethnographic interest had largely come to a halt, following on the progressive divide between paleo-ethnology and ethno-anthropology starting in the first decades of the 20th century. The foundations of the Pigorini museum, in particular, had already been shaken as early as 1911, with the Congress of Italian Ethnography, and by the time of the move to EUR the crisis of institutional mission had reached an apex.

In the 1990s, in fact, the museum began a critical re-examination of its history, extracting many insights that have served in revitalizing the mission, including through exhibitions focused on new scientific and academic perspectives.

Picking up the legacy of previous interpretations, the Museum of Civilizations, since its establishment in 2016, has carried out methodological and theoretical research in critical departure from the assumptions characteristic of the institution’s long-ago birth, and some of its still positivist research methods. Thus the museum no longer deals in comparisons between prehistoric and ethnographic “primitives”, and with this same logic, the presentations of the extra-European collections are currently being redeveloped, and will be subject to periodic renewal and deepening.

The Collection of African Arts and Cultures

Although the origin of the word “Africa” remains uncertain, the most plausible hypothesis is of a derivation from Tuscan and Italian literary traditions, in which Africa meant the “land of the Afri“, the Latin name for peoples inhabiting the southern side of the Mediterranean basin. Today, as in the past, the African continent is a land of multifaceted and multiform societies, of which the Museum of Civilizations’ Collections of African Arts and Cultures provide only a fragmentary representation. In recent decades the collections, comprising some 10,000 items, have been sorted in terms of three areas:

- First African objects in Italy

In the early Modern Age, Europeans knew only the coastal parts of Africa. Portuguese navigators had explored the western coasts in the years between 1434 and 1488 and then, reaching the Cape of Good Hope, opened the routes to Zanzibar and the Indies. The inland configuration of the continent remained unknown, the Portuguese having limited themselves to installing coastal ports in the service of their merchant vessels, and allowing entry of Catholic missionaries. These first voyagers of the 16th and 17th centuries brought back objects that to them seemed particularly curious, or perhaps wonderful for the refinement of their workmanship or rarity of materials. Most of these objects flowed into the collections of the royal and princely courts of Renaissance and Baroque Europe, the treasuries of cathedrals, or the cabinets of curiosities held by eminent personages, such as the one developed in Rome by the Jesuit father Athanasius Kircher, between 1635 and 1680. In the later 19th and early 20th centuries, it was these materials that often became the nuclei for the collections of the many world ethnographic museums established in Europe.

- European “explorations” of the interior: colonialism and the genesis of ethnographic collections

European explorations of inland Africa took place over the course of a century, beginning with the individual voyages from the late 1700s up to the mid-1800s, such as those Mungo Park, René Caillé, Heinrich Barth, and the later full-scale expeditions such as those promoted by geographical societies. The routes used to access the interior often followed major rivers, resulting in the drawing of the related hydrographic maps of Africa. The sources and course of the upper Nile were mapped last, between 1857 and 1864, following the voyages of Richard Burton, John H. Speke and James A. Grant. On the threshold of the 20th century, exploration of the interior became an occupation, first economic and then military. This occurred explicitly in 1884, with the Berlin or West African or Congo Conference (German Kongokonferenz), when the European powers agreed on the partitioning of the African continent.

Integral to policies of colonial expansion, ethnographic museums sprang in the United States and the European nations. These collected and classified weapons, tools, works of art, religious and civil symbols, and every other kind of object of both daily or ritual uses.

The objects preserved in ethnographic museums are for this reason also a record of interpretations mistakenly believed to be scientific, but in truth reflecting racist imaginaries. In contemporary museum displays, such views must be historically reconstructed in order to reconcile the collections with the contemporary world. The reconstruction of past interpretations illustrates past mentalities of superiority, characteristic of European cultures of the time, and the differences in the way objects were viewed between those who made and used them, as true actors of identity, and those who on the other hand removed them from their original contexts and placed them in the collections of European ethnographic museums.

- African art

Art from Africa is expressed in a vast articulation of forms, materials, techniques and symbols. Within the ethnographic museums of the time, however, it was wooden sculpture – in the forms of masks and statuary – that came to most represent the artistic traditions of the African continent. In the early 20th century, moreover, the massive presence of these works and their forms of creative expression – appearing also in the universal exhibitions on colonialism such as those of Brussels in 1897, Paris in 1907, 1917, 1919, or the first exhibition of African sculpture in Italy, held at the Venice Biennale in 1922, from which some materials found their way into the collections of the Museum of Civilizations – influenced the definition the European avant-gardes, in particular Cubism, Expressionism, Fauvism, and Futurism. These developments, however, occurred with obvious misunderstandings and simplifications, starting with the one-sided and homogenizing definition of art nègre, or “primitive art”, and ignoring the complex articulations of arts and cultures within the continent as a whole.

The Museum of Civilizations is currently reorganizing its presentations of African Arts and Cultures. New works and archival materials will include some devoted to populations, cultures and arts not formerly considered, along with insights into the realities of Italian colonialism of the 19th-20th centuries, the roles of major European exhibitions and 20th-century academic research, and finally contemporary globalization.

From the collections

The informations contained in the captions are derived from historical documentation or cataloging and inventories that do not necessarily reflect complete or current knowledge on the part of the Museum of Civilizations. The progressive revision of the collections database is ongoing and will be constantly updated based on the research conducted and by activating comparisons and collaborations with external parties as well, with particular attention to provenance studies.

Archive under updating