The origins and history of the Collections #1

From the Royal National Prehistoric Ethnographic Museum (1875) to the Museum of Civilizations (2016)

The Royal National Prehistoric Ethnographic Museum of Rome, originally housed in the building of the former Roman College, was founded in 1875 by archaeologist Luigi Pigorini. These were the years immediately following the unification of Italian territories as a new kingdom, and in keeping with the intentions of its founder, the aim of the institution was to serve as a national repository for the documentation and study of the prehistoric cultures of Italy, but also of Europe and the larger world, and of non-European ethnographic cultures in general, all of which considered as “primitive.”

The Roman College, built by the Order of Jesuits, had since the 1600s housed the collection of antiquities and curiosities assembled by Father Athanasius Kircher, and it was this “Kircherian museum” that Pigorini assumed as the nucleus of the Royal Museum. The first collections of an ethnographic nature had thus been assembled between 1635 and 1680 by Father Kircher himself, from Capuchin missions in the Congo and Angola and Jesuit missions in China, Brazil and Canada. Along with the Kircherian core there were also exotic “curiosities” brought from the New World and preserved in the most important collections of 18th-century Italy – such as those of Cardinal Flavio Chigi Senior and Cardinal Stefano Borgia – as well as others brought from around the world by merchants, missionaries and travelers, up to the late 19th century and continuing after the museum’s founding.

The museum developed its ethnographic collections further through purchases and gifts. The House of Savoy, for example, donated numerous objects, including musical instruments from Hindustan and women’s ornaments from the nomadic cultures of North Africa. Pigorini also worked out personal agreements, and others through the Ministry of Education, with the commanders of transoceanic scientific expeditions organized by the Ministry of the Navy, seeking objects and photographs from the lands explored. In addition the Italian Geographical Society, headquartered on the main floor of the Roman College, conducted its own expeditions, and from these turned over objects of ethnographic interest to the Royal Museum. Particularly fruitful in this regard were the expeditions of Giacomo Bove in Tierra del Fuego, and Romolo Gessi in the regions of East Africa.

The first layout of the Royal Museum derived from worldviews that placed human civilizations on an imaginary evolutionary scale, also of service in colonial narratives and practices. Among the non-Europeans, the Asian continent was at the apex, as seen in the first rooms of the exhibition itinerary. The visitor would then continue their visit through the rooms devoted to the Americas, beginning with the north and continuing south, then the rooms devoted to the Oceanian collections, and finally those focusing on Africa.

Roughly a century later, and renamed the National Prehistoric Ethnographic Museum following the founding of the Italian republic, the museum left the premises of the Roman College to the new Ministry of Cultural and Environmental Heritage and transferred entirely to the EUR Palace of Sciences, originally constructed for the Universal Rome Exhibition of 1942. At this time, around 1975-77, the museum still retained its original organization in two sectors: Prehistory and Extra-European Ethnography. However by now the academic device of comparison between prehistoric societies and societies of ethnographic interest had largely come to a halt, following on the progressive divide between paleo-ethnology and ethno-anthropology starting in the first decades of the 20th century. The foundations of the Pigorini museum, in particular, had already been shaken as early as 1911, with the Congress of Italian Ethnography, and by the time of the move to EUR the crisis of institutional mission had reached an apex. In the 1990s, in fact, the museum began a critical re-examination of its history, extracting many insights that have served in revitalizing the mission, including through exhibitions focused on new scientific and academic perspectives.

Picking up the legacy of previous interpretations, the Museum of Civilizations, since its establishment in 2016, has carried out methodological and theoretical research in critical departure from the assumptions characteristic of the institution’s long-ago birth, and some of its still positivist research methods. Thus the museum no longer deals in comparisons between prehistoric and ethnographic “primitives”, and with this same logic, the presentations of the extra-European collections are currently being redeveloped, and will be subject to periodic renewal and deepening.

The origins and history of the Collections #2

From the National Museum of Oriental Art (1957) to the Museum of Civilizations (2016)

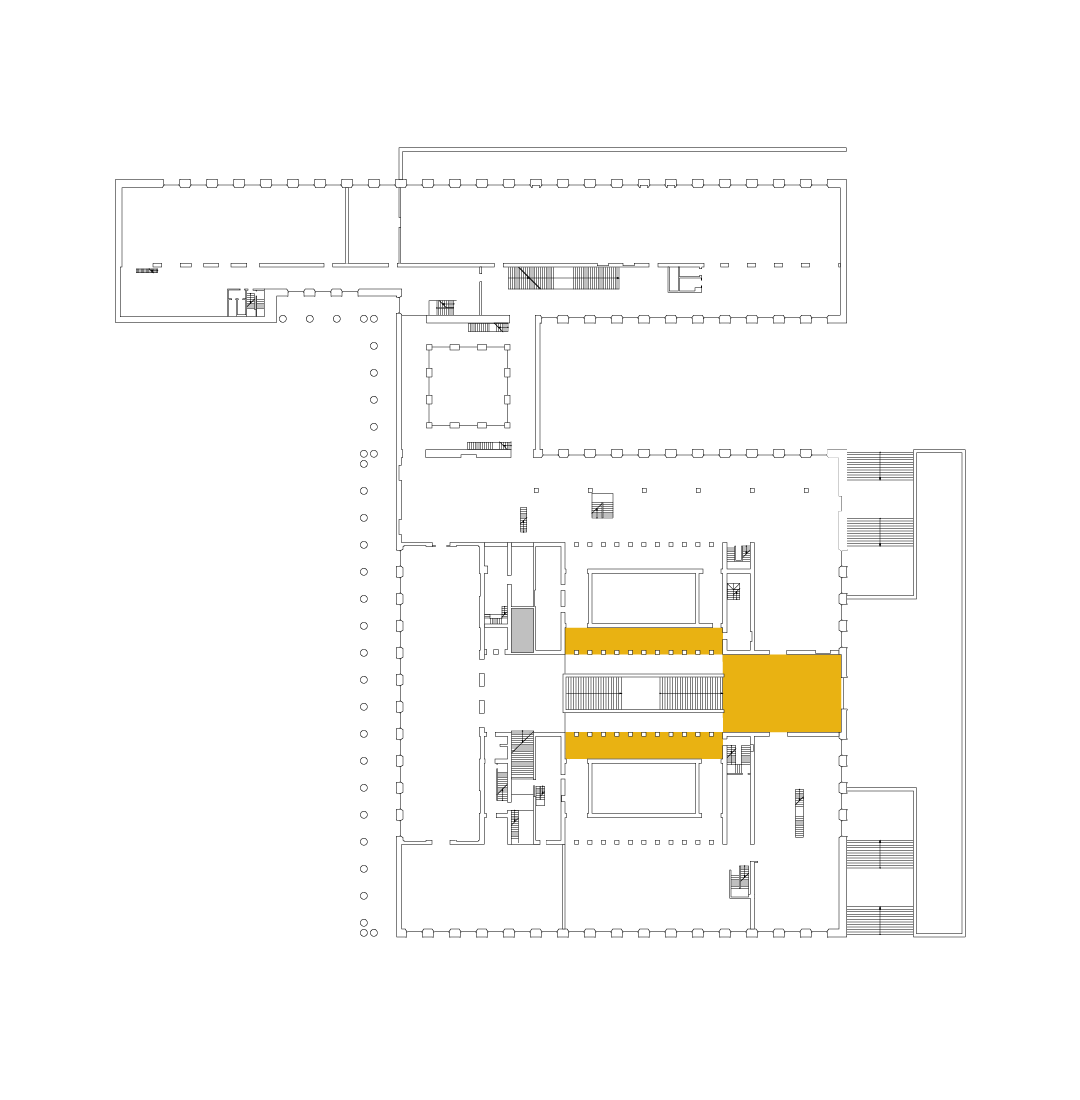

The Asian Arts and Cultures Collections of the Museum of Civilizations are composed of works from the ‘Luigi Pigorini’ National Prehistoric and Ethnographic Museum and the ‘Giuseppe Tucci’ National Museum of Oriental Art, both of which merged into the Museum of Civilizations in 2016. In the context of the Great Cultural Heritage Project funded by the Ministry of Culture, the Museum of Civilizations is currently overseeing the comprehensive reorganization of these unified collections, culminating in 2026 with their reopening to the public on the ground floor of the Palace of Sciences.

The National Museum of Oriental Art was established in 1957 by Decree of the President of the Republic (No. 1401), which noted that the measure would “endow our country with an institute it has lacked, although Italy boasts a long tradition of Orientalist research and studies.” In fact the establishment had come at the instigation of Giuseppe Tucci (1894-1984), an international leader in studies of Asian religions, philosophies and systems of thought. In 2010, in recognition of this scholar, the museum would take his name. As early as 1933 Tucci and Giovanni Gentile had founded the Italian Institute for the Middle and Far East (ISMeO), aimed at the promotion of cultural, economic and political relations with the Asian countries. The new institution was intended to serve as a partner to ISMeO in the implementation of archaeological research and restoration of monuments, as well as a further point of reference for Orientalist studies.

The museum opened to the public in Rome, at first with some materials at IsMEO itself, but then on the piano nobile of a grand palazzo in Rome, originally built for Prince Salvatore Brancaccio and wife Elizabeth Fields. Architect Francesco Minissi reworked the interior of the noble apartments using fabrics and partitions, and Mario Bussagli, the museum’s first director, curated the inaugural exhibitions, which grouped the collections by geographic origins, then chronologically. A first thematic exhibit dealt with the art of Gandhara, a cultural crossroads between northern Pakistan and south-eastern Afghanistan. In general, the early exhibitions relied on materials from excavations promoted by IsMEO, whose president in those years was Tucci himself. A site of early relevance was that of Bukhara, Uzbekistan, excavated in 1956, where an important Buddhist sacred area was found.

Subsequently, the museum enriched its collection through exchanges and deposits, as well as purchases and donations. Among the objects flowing into the collection were finds from the Italian Archaeological Mission (also founded by Tucci), operating in 1957-1968 and 1967-1978 in Ghazni, southwest of Kabul, and in Shahr-i Sokhta in eastern Iran, an important center on the trade routes linking the Egypt and the Near East with Central Asia, between the fourth and second millennia BC.

The museum’s itinerary offered visitors a comprehensive study of Asian arts and cultures, not only in terms of geographical and chronological extension – from Moorish Spain to Japan, and from the protohistoric to contemporary times – but also of their different aspects and nuances, from the “high cultures” of the courts to the everyday cultures of villages, and from philosophical-religious to technological systems. The museum also paid special attention to research activities – carried out through agreements with the institutes of the Ministry of Culture and Italian and foreign universities – as well as to training and the communication of knowledge in the academic context and with different publics: organizing conferences, workshops, seminars, special events and education services. The museum developed a specialized library, integrated with the National Library Service, comprising some 20,000 titles in 46 languages. From the outset the NMAO maintained international contacts, carrying out projects in cooperation with cultural institutions around the world: from 1983 to 2016 the Museum was a leader or partner in more than 40 international projects, including archaeological and restoration missions in many areas of Asia.

From its outset, the museum was also charged with “special purposes”, specifically for legal protection of archaeological and historic-artistic materials of Asian origin. In this role, it has provided opinions and carried out activities in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture offices for import-export controls, and with the special departments of the Police Forces, which led to actions for the return of exported goods to their countries of origin. The museum has also offered specialist consultancies to public and private entities for the conservation, restoration, cataloguing and display of archaeological, artistic and biological goods, including through the activities of its scientific laboratories. In 1982, the museum launched a collaborative project for “Oriental Art in Italy”, supporting comprehensive national action for the census, preservation and fruition of the relevant materials.

In 2016, the collections, photo archives and specialized library of the ‘Giuseppe Tucci’ National Museum of Oriental Art were merged into the Museum of Civilizations.

The Collection of Asian Arts and Cultures

One of the earliest attestations of the word “Asia” is found in Herodotus’ histories of the Persian Wars, where he uses the term to refer to Anatolia and the Persian Empire, distinguishing them from Greece and Egypt. One hypothesis is that the term descends from the word asu in the Akkadian language of ancient Mesopotamia, meaning “to rise,” later coming to mean the lands to the east, “of the rising sun”, and then becoming more and more general until arriving at its current use to refer to the entire continent of Asia.

In anticipation of a comprehensive re-installation on the ground floor of the Palace of Sciences in 2026, selected items from the Asian Arts and Cultures Collections of the Museum of Civilizations have been re-installed as part of the EUR_Asia project.

The Asian collections of the ‘Luigi Pigorini’ National Prehistoric and Ethnographic Museum

The more than 15,000 works in the Asian collections of the ‘Luigi Pigorini’ National Prehistoric and Ethnographic Museum derive mostly from purchases and gifts from diplomats, travelers, traders, scholars and artists present in Asia around the turn of the 19th-20th centuries. These objects were most often obtained when relations with Western countries were still in their nascent stages. Certain objects of ethnographic interest also derived from expeditions organized by the Italian Geographical Society. In 1888 and 1916 the museum received gifts of collections from Japan, gathered by Vincenzo Ragusa during his stay between 1876 and 1882, when the nation had only recently reopened its borders to the outside world. In 1924, Giuseppe Ros, an Italian consular interpreter in China, donated his collection of 2,000 objects relating to domestic life, complementing the earlier purchase of the Fea Collection, in 1889, consisting of objects of Burmese origin. The Royal Museum also acquired the collection of Enrico Hillyer Giglioli, including Chinese and Japanese jades, and objects relating to Buddhism from Tibet. In 1879, King Victor Emmanuel II awarded the museum with a collection of musical instruments given to him by Raja Sourindro Mohun Tagore.

The Asian collections of the ‘Giuseppe Tucci’ National Museum of Oriental Art

The collections of the National Museum of Oriental Art began with the deposit of materials gathered still earlier by the Italian Institute for the Middle and Far East (IsMEO), and with recoveries from excavations carried out by Italian archaeological missions in Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan. The museum would also receive the personal collections of Giuseppe Tucci, among which a part of the objects gathered by the scholar in Nepal and Tibet, between 1928 and 1954.

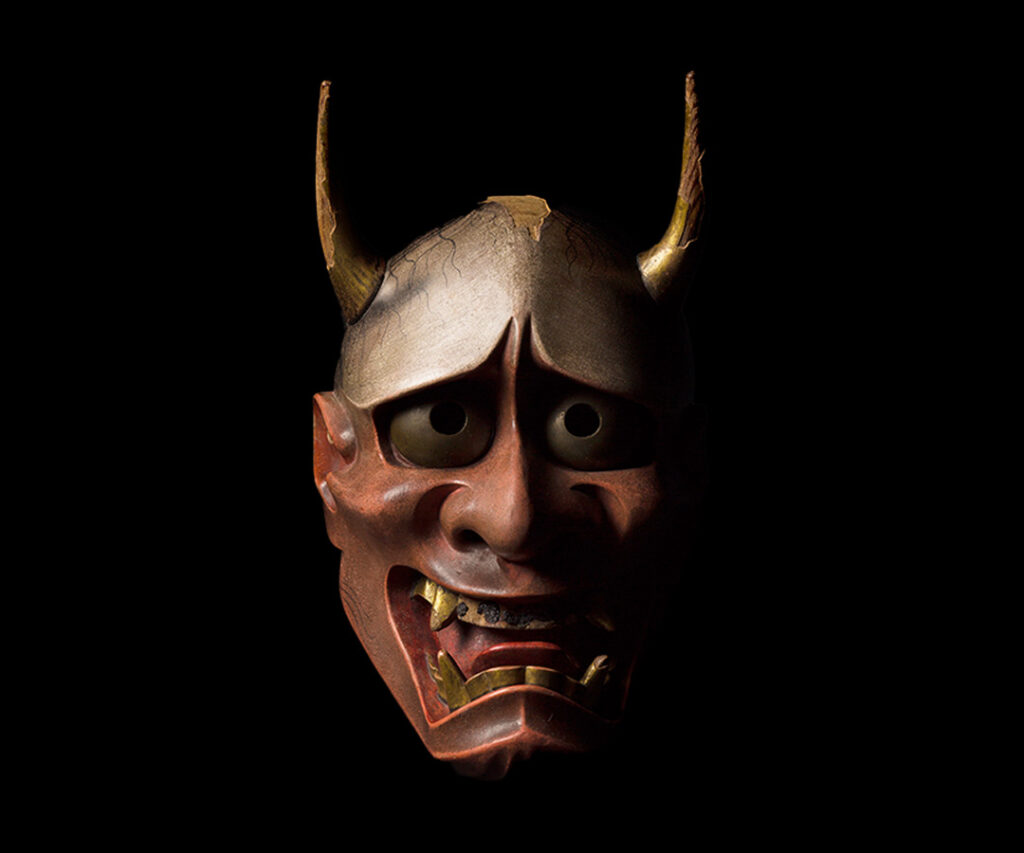

The collections were gradually augmented by the Italian state, thanks to negotiations by the offices controlling imports and exports, and the purchase of artifacts on the antiquities market. Among these was the valuable Parthian-era relief depicting Batmalku and Hairan from Palmyra, Syria: the work, formerly part of the Stroganoff collection, was purchased from the antiquarian Sangiorgi in 1971, supplementing the Near East collection. In the same manner, the substantial Iran-focused collections received additional materials from Mesopotamia, Anatolia, the Syrian-Lebanese area and Transcaucasia. Some objects are also the result of exchanges, among which contributions concerning Thailand and Pakistan. Donations include those of Burmese art by Giovanni Andreino, first representative of the Italian government in Mandalay (1871-1885); a gift from Giacomo Mutti of objects from various contexts of the Indian subcontinent (works in marble, stone and bronze; folk objects including textiles, miniatures, oracular masks); Korean ceramics from the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties given by the Republic of Korea in 1960; a collection of objects from China donated in 1970 by Manlio Fiacchi and Antonia Gisondi; a donation of contemporary Korean works by the artists themselves; a collection of Iranian ceramic types from the Iron Age to the Imperial Age, given in 2017 by Pompeo Carotenuto. In addition, in 2005 Francesca Bonardi-Tucci, wife of Giuseppe Tucci, donated more than 2,000 objects, mostly from the Himalayan and Iranian areas, while upon her death another 3,000 objects came to the museum (including 1,600 pieces of jewelry from various cultural areas), which she named as her universal heir.

The collections currently consist of about 40,000 works divided into the following geographic-cultural themes.

- Near and Middle East: objects testifying to the long history of these areas, but with special emphasis on Greater Iran. The Bronze Age is documented both by finds from Shahr-i Sokhta (4th-2nd millennium BC), an urban center of the southeast, and by production in painted vases referable to the Tepe Siyalk and Tepe Giyan cultures, respectively of central and western Iran. The Iron Age (15th-6th centuries BC) is documented in the profound typological and formal innovations characteristic of the vases and metallurgy of the cultures of the Iranian region, together with the contributions of the nomadic cultures of the Eurasian steppes. The imperial art of the Achaemenids, Parthians, and Sasanids (6th century BC-7th century AD) reflects the new international-political dimensions of Greater Iran. Ceramics, sculpture, silver, bronzes, jewelry, and glass bear witness to both continuity and innovation in the vital art of the Eurasian steppes, and to links with the Syro-Mesopotamian cultures of the preclassical age and with the Greek world, as well as relations with the Far East and the Roman and Byzantine West.

- Islamic Art and Archaeology: objects from the 8th to the 19th centuries, including ceramic and metal works, as well as elements of architectural decoration in terracotta and marble from a palace excavated by an IsMEO mission in Ghazni, Afghanistan. The Afghan collection is the richest in the world apart from those held in the country itself, in Kabul and Ghazni. Also present are objects from the Iraqi area, Moorish Spain, India, Pakistan, and Ottoman Turkey. The extensive Iranian collection also includes an oil painting and papier mâché works from the Qajar period.

- South Arabic Antiquities: one of the richest collections in the world outside of Yemen, consisting of a wide range of works from the 8th century BC to 7th century AD, gathered largely through donations and purchases by Italian doctors and politicians, resident in Yemen and Eritrea before and after World War II.

- India: includes works of the “Great Tradition” and objects of day-to-day life covering the 9th to 20th centuries, ranging from sculptures and stelae of Templar provenance to miniatures, bronzes, and folkloric paintings on themes of the divine and the personalities of the Hindu pantheon.

- Gandhara (areas of ancient Northwest India): focuses on a selection of shale reliefs with scenes from the life of Buddha, figures of bodhisattvas and donors, excavated by the Italian archaeological mission at the Butkara I site, in the Swat Valley of Pakistan. Gandharan figurative art, characterized by classical-Hellenistic-Roman-Indian and Iranian influences, flourished between the 1st and 5th centuries AD in the territories of ancient Northwest India (present-day northern Pakistan and southern Afghanistan).

- Tibet and Nepal: materials including ritual objects, statues in metal alloys, frescoes, jewelry, furnishings and furniture parts. The collection is closely connected with the history of Italian scientific research in Asia, and especially with the life and work of Giuseppe Tucci, an Asianist internationally recognized as one of the founders of contemporary Tibetology. An important donation by Francesca Bonardi-Tucci, in 2005, strengthened the holdings in the areas of Himalayan art. Overall the collection is one of the world’s most important both in quality and variety. Particularly notable are the paintings on cloth (thang ka) and they clay seals (sa tsha tsha).

- Southeast Asia: Khmer-era artifacts from Cambodia and Thailand, mainly bronzes, sandstone sculptures and ceramics, cultic objects, busts and heads of the Buddha pertaining to Thai art of the 9th to 18th centuries, gilded wooden statues, texts on lacquered palm leaves, votive containers of Buddhist scope, musical instruments and statuettes of Ramayana actors from Myanmar datable to the Konbaung era (1752-1885). These materials also include a valuable collection of Indonesian goldsmithing from the 4th to 15th centuries, a series of life-size terracotta figures, and Javanese shadow theater puppets (wayang kulit).

- China: materials ranging from the Neolithic to the 20th century, including bronzes, jades, paintings and textiles. Exhibitions have focused on works related to Buddhism, introduced to China from India around the 1st century via the Silk Road, including four stone heads of Buddhas and bodhisattvas from the Tianlongshan cave temple, and a selection of ceramics ranging from Tang Dynasty (618-907) funerary figurines to monochrome vessels from the last imperial Qing Dynasty (1664-1911).

- Korea: includes bronzes and ceramics from the Three Kingdoms period (300-668) to the end of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1010). The small collection is enhanced by some works of the late 20th-early 21st centuries, donated by the artists and master craftworkers who made them.

- Japan: a collection ranging from archaeological artifacts to mirrors and bronze liturgical objects of the Heian (794-1185) and Kamakura (1185-1333) periods. Presented in exhibit have been a wooden Buddha from the early Edo period (1615-1868) and a selection of ceramics, including two from the workshop of Kitaoji Rosanjin (1883-1959), donated by the artist to IsMEO

- Vietnam: consisting mainly of the testamentary bequest of Ivanoe Tullio Dinaro (1940-1993), the collections consist of glazed ceramics from the 12th to 18th centuries, considered some of the most sophisticated manifestations of Asian art.

From the collections

The informations contained in the captions are derived from historical documentation or cataloging and inventories that do not necessarily reflect complete or current knowledge on the part of the Museum of Civilizations.

The progressive revision of the collections database is ongoing and will be constantly updated based on the research conducted and by activating comparisons and collaborations with external parties as well, with particular attention to provenance studies.

Archive under updating