Le origini e la storia delle collezioni

From the Royal National Prehistoric Ethnographic Museum (1875) to the Museum of Civilizations (2016)

The Royal National Prehistoric Ethnographic Museum of Rome, originally housed in the building of the former Roman College, was founded in 1875 by archaeologist Luigi Pigorini. From the outset the museum was fundamental in promoting and coordinating the excavation of prehistoric sites throughout the nation. Under Pigorini’s leadership, the museum was also intensely innovative in education and communications, with actions including the hosting of Italy’s first chair of paleo-ethnology, and the founding – in the same year as the museum itself – of the Bullettino di Paletnologia Italiana, one of the first European journals dealing with prehistory.

The Roman College, built by the Order of Jesuits, had since the 1600s housed the collection of antiquities and curiosities assembled by Father Athanasius Kircher, as reported in the publication Musaeum Collegii Romani Societatis Jesu of 1679. Following the unification of the Kingdom of Italy over the years 1860-1871, it was this Kircherian museum that Pigorini assumed as the nucleus of the Royal Museum, reconfigured as a founding cultural institution for the new nation.

Roughly a century later, and renamed the National Prehistoric Ethnographic Museum following the founding of the Italian republic, the museum left the premises of the Roman College to the new Ministry of Cultural and Environmental Heritage and transferred entirely to the EUR Palace of Sciences, originally constructed for the Universal Rome Exposition of 1942. At this time, around 1975-77, the museum still retained its original organization in two sectors: Prehistory and Extra-European Ethnography. However by now the academic device of comparison between prehistoric societies and societies of ethnographic interest had largely come to a halt, following on the progressive divide between paleo-ethnology and ethno-anthropology starting in the first decades of the 20th century. The foundations of the Pigorini museum, in particular, had already been shaken as early as 1911, with the Congress of Italian Ethnography, and by the time of the move to EUR the crisis of institutional mission had reached an apex. In the 1990s, in fact, the museum began a critical re-examination of its history, extracting many insights that have served in revitalizing the mission, including through exhibitions focused on new scientific and academic perspectives.

Picking up the legacy of previous interpretations, the Museum of Civilizations, since its establishment in 2016, has carried out methodological and theoretical research in critical departure from the assumptions characteristic of the institution’s long-ago birth, and some of its still positivist research methods. Thus the museum no longer deals in comparisons between prehistoric and ethnographic “primitives”, and with this same logic, the current presentations seek to reinterpret the very concept of “prehistory”.

The Prehistory and Protohistory Collections

The Museum of Civilizations conserves Italy’s largest and most comprehensive prehistoric collections, consisting of more than 150,000 artifacts from Italian and international archaeological sites, and representing a timespan from the earliest phases of the so-called Stone Age to the earliest forms of writing. The current exhibitions present artifacts with a long history of display, along with others rarely or never before seen: the original Guattari 1 Neanderthal skull from the Circeo Guattari Cave; the three “Venuses” from the Savignano, Lago Trasimeno and La Marmotta sites; pirogues recovered from Lake Bracciano, along with hundreds of artifacts from the Neolithic village of La Marmotta, the necropolis and the Copper Age settlement of Gricignano d’Aversa; materials from the so-called “Widow’s Tomb”; from the Polada site and the hoard of Coste del Marano; the bronzetto of a warrior and ritual swords from the Nuragic culture. The exhibition concludes with the Prenestina fibula, made in gold and bearing one of the earliest known instances of Latin writing.

Prehistory conventionally stands for “before history”, meaning the period from the earliest evidences of material culture produced by our ancestors to the earliest records using graphic signs, in representation of spoken languages. Prehistory thus covers a period of time incomparably longer than the duration of all subsequent periods. Much of human history is composed of Prehistory.

It is important, however, to emphasize that the events of Prehistory – from the origins of the arts to the domestication of plants and animals, from the formation of stable settlements to the transformation and use of metals – occurred at different times and in different ways in the various geographical regions. Therefore, the beginning and ending of Prehistory vary in date depending on the area, as do the intermediate stages. During the earliest periods of Prehistory, moreover, different human forms coexisted, but also succeeded one another in adaptation to climatic and environmental changes. Eventually, communities of Homo sapiens came to populate much of the world’s landmasses, developing ever more diverse and complex cultural systems. Even in the oldest societies, however, we can identify phenomena of tradition and innovation, rootedness and territorial mobility, rules and social flexibility, a sense of identity and openness to contact and exchange. Prehistory is therefore not only an integral part of history, encompassing all the fundamental characteristics of humanity, but is itself a history composed of articulated and intertwined histories.

Even in the absence of written records we can study the past before history. By analyzing and interpreting geological, paleontological and genetic data, together with the archaeological evidence of material cultures, we can reconstruct the environmental contexts of societies and an infinity of details about daily life, and gain understanding of multiple systems of thought, cultural inventions, economic, political and social organizations. What we observe is that, rather than following a linear path, the evolution of societies results as an interweaving of wholes, continuously transforming and adapting, involved in contacts, migrations, competitions, crises and even extinctions.

Modern archaeological research therefore requires interdisciplinary collaboration, applying varied tools and techniques, and involves the constant reworking of theoretical models to arrive at ever more reliable interpretations of what we call “Prehistory”.

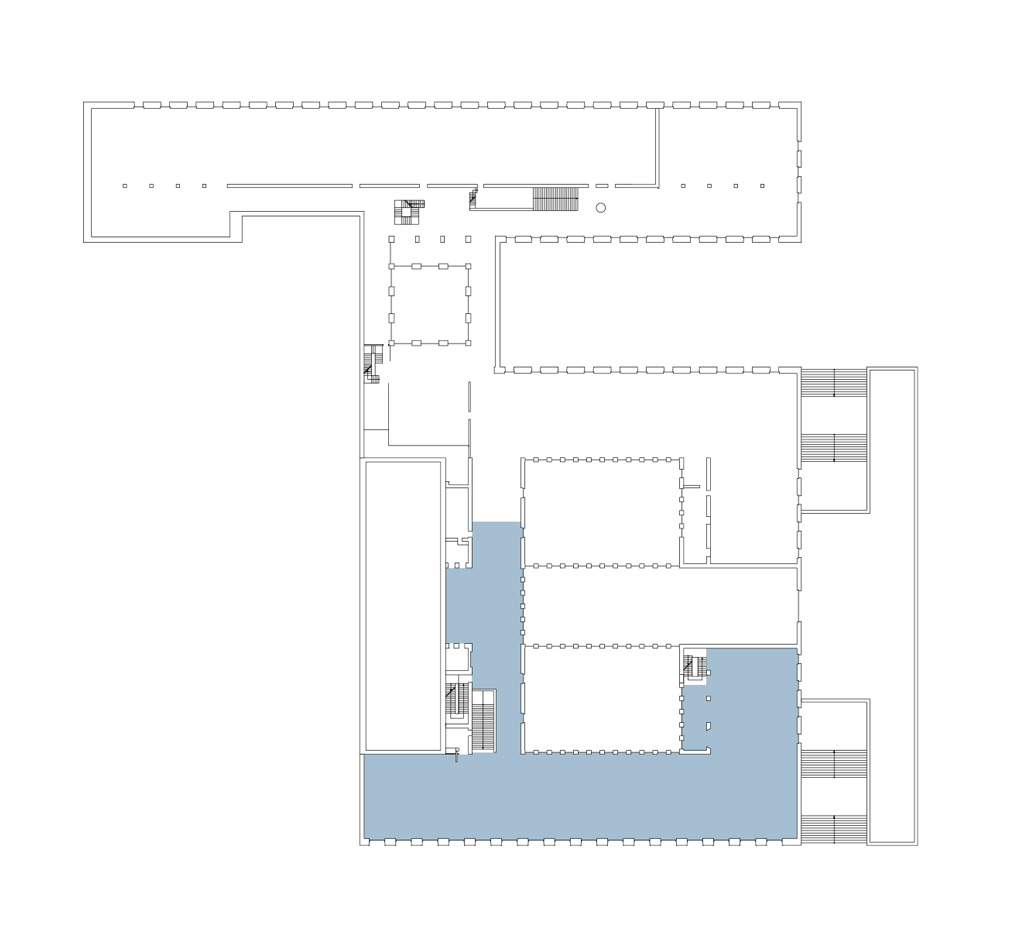

The rearrangement of the Prehistory and Protohistory Collection

Prehistory? Stories from the Anthropocene

From the collections

Archive under updating