– in progress

Prehistory? Stories from the Anthropocene

Entitled Prehistory? Stories from the Anthropocene, the new display of the Prehistoric and Protohistoric Collections of the Museum of Civilizations includes a selection of Italy’s largest and most articulated prehistoric collection, consisting of more than 150,000 artifacts from Italian and international archaeological sites, dating from the earliest Stone Age to the times of the earliest writing.

The new exhibition will present artifacts with a long history of display, along with others rarely or never before seen: the original Guattari 1 Neanderthal skull from the Circeo Guattari Cave; the three “Venuses” from the Savignano, Lago Trasimeno and La Marmotta sites; pirogues recovered from Lake Bracciano, along with hundreds of artifacts from the Neolithic village of La Marmotta, the necropolis and the Copper Age settlement of Gricignano d’Aversa; materials from the so-called “Widow’s Tomb”; from the Polada site and the hoard of Coste del Marano; the bronzetto of a warrior and ritual swords from the Nuragic culture. The exhibition concludes with the Prenestina fibula, made in gold and bearing one of the earliest known instances of Latin writing.

The first nucleus of the collections came from the study and research activities of Luigi Pigorini, founder and director of the Royal Prehistoric and Ethnographic Museum. Established in 1875 in the former Roman College, the aim of the new institution was to promote a unified scientific approach to Italian paleo-ethnological research. One of its roles was to gather the materials discovered in a central structure in the new capital of the Kingdom of Italy, but also to use the documentation of prehistoric cultures for purposes of creating and promoting a national identify suited to the new unified state, thus responding to a precise political intent.

In the one and half centuries since first formation of the collections the holdings have continued to grow, through donations, purchases, exchanges and field research. The new exhibit aims to trace their history up to the most recent discoveries and to contextualize and question, from various points of view, the very definition of “prehistory”. The conception is one of “history before history”, meaning the story of the times from the origins of humans to the formation of civilizations characterized by writing. But does history really begin with writing, as we were taught in school? And is it correct to divide the narrative of human experience on planet Earth so sharply, entrusting the vast majority of many millions of years to a hypothetical “before history”?

We no longer call this section “Prehistory” precisely because it too tells us a “story”: composed of the innumerable stories that emerge from the study and interpretation of the material evidence left by those who lived before us, and which return to us multiple systems of thought, cultural inventions, economic, political and social organizations. What we observe is that, rather than following a linear path, the evolution of societies results as an interweaving of wholes, continuously transforming and adapting, involved in contacts, migrations, competitions, crises and even extinctions.

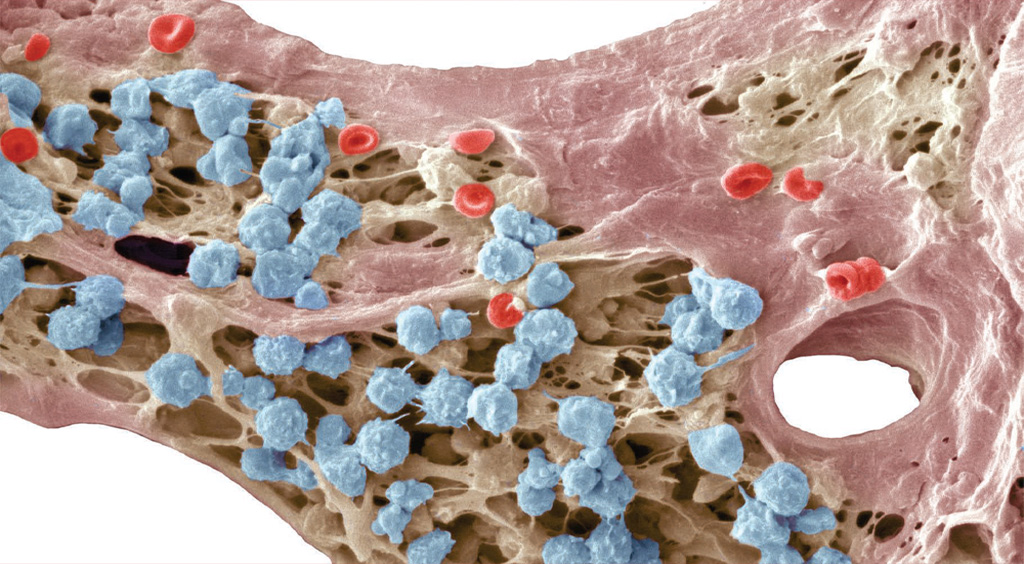

Developed gradually from the 13th century onward, the concept of “prehistory” was also used instrumentally in the second half of the 19th century to support the formation of Western national identities, identifying the “other than oneself” as something primitive, still immersed in a prehistoric time, and therefore foreign to the evolutionary linearity of Western modernity. These theories have often coincided with ideas of racial superiority, in which non-European civilizations would also be associated with prehistory. More recent research, such as that on DNA, and into the nature/culture relationship as a unitary ecosystem, reveals a picture of human origins that is itself polycentric and inter-species, reframed in terms beyond the standard subdivisions of individual species.

This entire museum section is thus reconfigured as the complex and layered narrative of the Anthropocene, that is, the millennial era of human cohabitation of the Earth with other species, in which we have often thought to control them, and which today – faced with increasing forms of inequality and environmental, climatic and pandemic risks, induced in many cases by humans ourselves – may soon come to an end.

To reflect on these scenarios that connect past, present and future, the section begins with a “scientific recounting of human evolution” tracing the processes that led to the present species and continuing with representations of civilizations from the Paleolithic to the Metal Ages. Viewers see some of the daily work and research materials of archaeologists and anthropologists, and some of the more long-standing displays have been rearranged. But because this is a history still continuing with us, the section ends with an “imaginative recounting of human evolution“, entrusted to various authors and in periodic update, allowing us to imagine possible developments and make us conscious and responsible creators of new stories, with ourselves as protagonists.

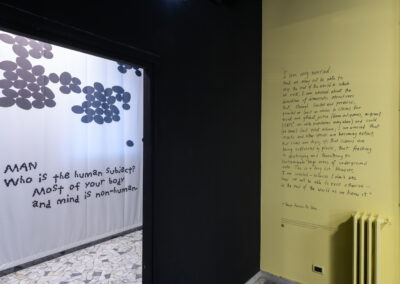

The section features a number of interventions by contemporary artists who lead the museographic narrative towards new questions, in this way interrogating and involving our own sensibilities and perceptions. The first artists called to this task are Ali Cherri (b. 1976, Beirut, Lebanon) – whose film The Digger, which relates the operation of archaeological excavation to that of the formation of a national identity, in this case in the United Arab Emirates, has been added to the museum collections – and the artist and anthropologist Elizabeth A. Povinelli (b. 1962, Buffalo, USA), a member of the indigenous Australian Karrabing Film Collective (Research Fellow at the Museum of Civilizations), who intervened on the walls of the pathway with a series of texts and images that reflect on the concept of “prehistory” by reinterpreting it as “sedimentation,” that is, as a relationship with ancestors and at the same time with the current environmental and historical context.