The origins and history of the Collections

From the Royal National Prehistoric Ethnographic Museum (1875) to the Museum of Civilizations (2016)

The Royal National Prehistoric Ethnographic Museum of Rome, originally housed in the building of the former Roman College, was founded in 1875 by archaeologist Luigi Pigorini. These were the years immediately following the unification of Italian territories as a new kingdom, and in keeping with the intentions of its founder, the aim of the institution was to serve as a national repository for the documentation and study of the prehistoric cultures of Italy, but also of Europe and the larger world, and of non-European ethnographic cultures in general, all of which considered as “primitive.”

The Roman College, built by the Order of Jesuits, had since the 1600s housed the collection of antiquities and curiosities assembled by Father Athanasius Kircher, and it was this “Kircherian museum” that Pigorini assumed as the nucleus of the Royal Museum. The first collections of an ethnographic nature had thus been assembled between 1635 and 1680 by Father Kircher himself, from Capuchin missions in the Congo and Angola and Jesuit missions in China, Brazil and Canada. Along with the Kircherian core there were also exotic “curiosities” brought from the New World and preserved in the most important collections of 18th-century Italy – such as those of Cardinal Flavio Chigi Senior and Cardinal Stefano Borgia – as well as others brought from around the world by merchants, missionaries and travelers, up to the late 19th century and continuing after the museum’s founding.

The museum developed its ethnographic collections further through purchases and gifts. The House of Savoy, for example, donated numerous objects, including musical instruments from Hindustan and women’s ornaments from the nomadic cultures of North Africa. Pigorini also worked out personal agreements, and others through the Ministry of Education, with the commanders of transoceanic scientific expeditions organized by the Ministry of the Navy, seeking objects and photographs from the lands explored. In addition the Italian Geographical Society, headquartered on the main floor of the Roman College, conducted its own expeditions, and from these turned over objects of ethnographic interest to the Royal Museum. Particularly fruitful in this regard were the expeditions of Giacomo Bove in Tierra del Fuego, and Romolo Gessi in the regions of East Africa.

The first layout of the Royal Museum derived from worldviews that placed human civilizations on an imaginary evolutionary scale, also of service in colonial narratives and practices. Among the non-Europeans, the Asian continent was at the apex, as seen in the first rooms of the exhibition itinerary. The visitor would then continue their visit through the rooms devoted to the Americas, beginning with the north and continuing south, then the rooms devoted to the Oceanian collections, and finally those focusing on Africa.

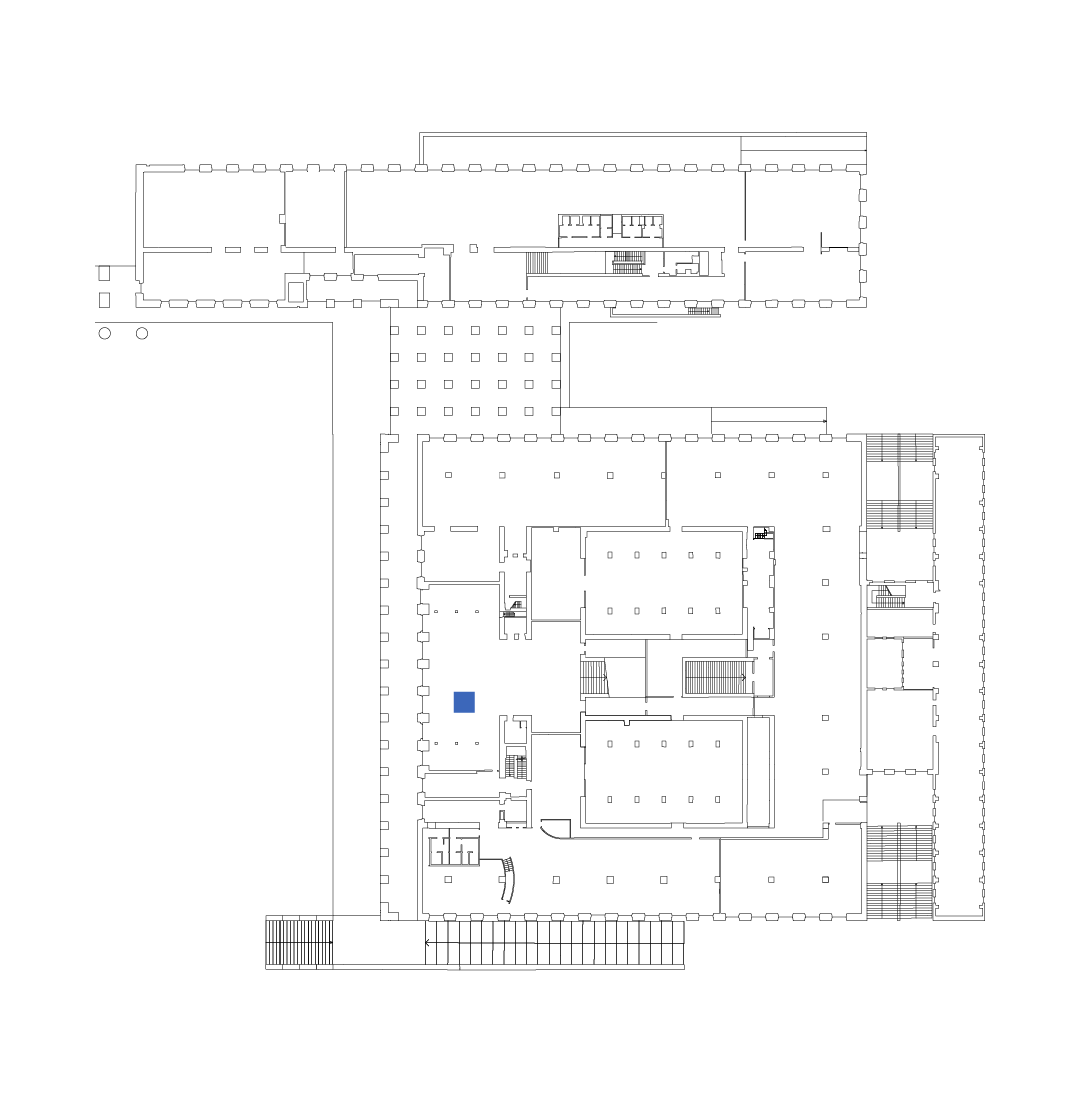

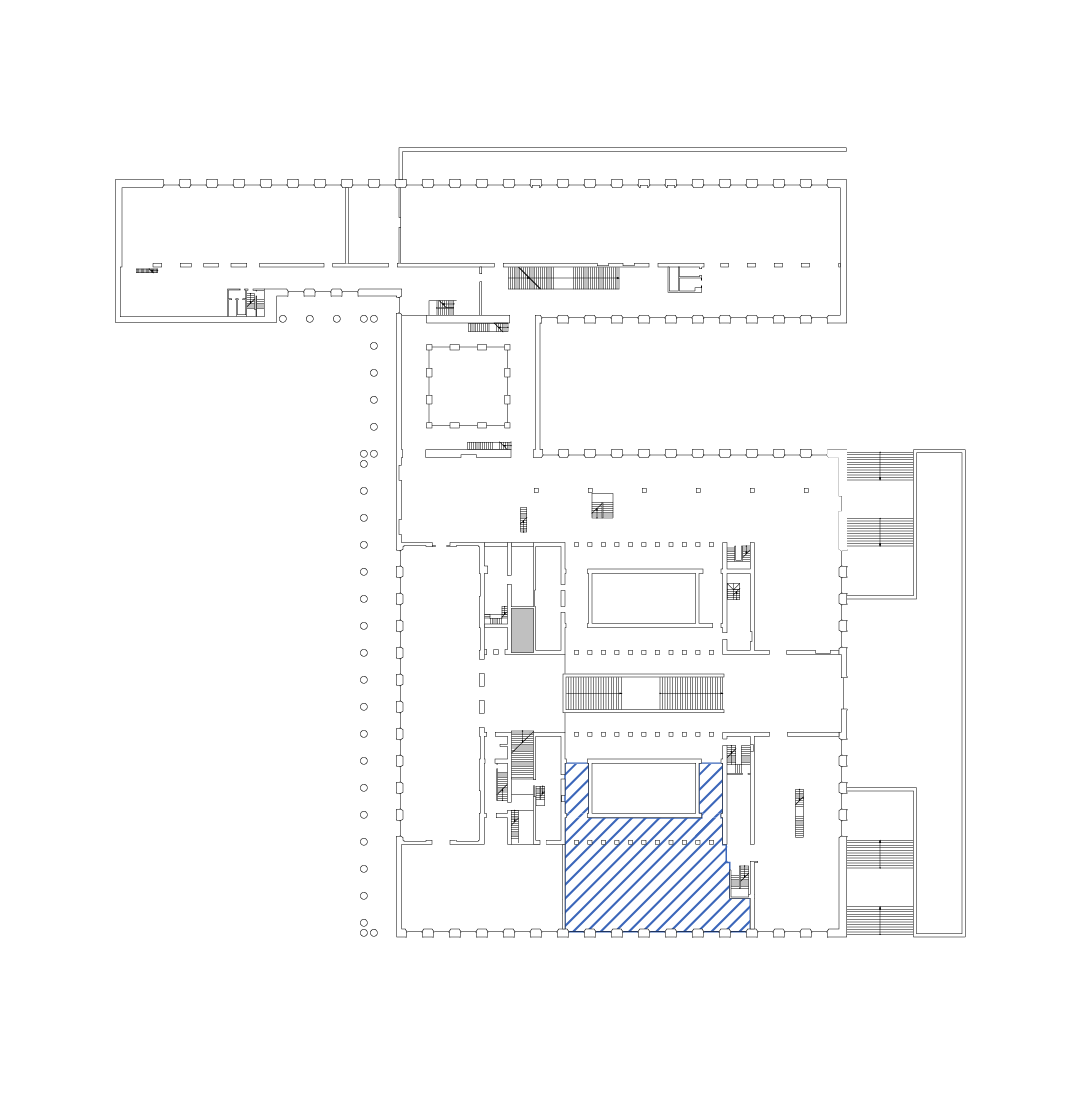

Roughly a century later, and renamed the National Prehistoric Ethnographic Museum following the founding of the Italian republic, the museum left the premises of the Roman College to the new Ministry of Cultural and Environmental Heritage and transferred entirely to the EUR Palace of Sciences, originally constructed for the Universal Rome Exhibition of 1942. At this time, around 1975-77, the museum still retained its original organization in two sectors: Prehistory and Extra-European Ethnography. However by now the academic device of comparison between prehistoric societies and societies of ethnographic interest had largely come to a halt, following on the progressive divide between paleo-ethnology and ethno-anthropology starting in the first decades of the 20th century. The foundations of the Pigorini museum, in particular, had already been shaken as early as 1911, with the Congress of Italian Ethnography, and by the time of the move to EUR the crisis of institutional mission had reached an apex. In the 1990s, in fact, the museum began a critical re-examination of its history, extracting many insights that have served in revitalizing the mission, including through exhibitions focused on new scientific and academic perspectives.

Picking up the legacy of previous interpretations, the Museum of Civilizations, since its establishment in 2016, has carried out methodological and theoretical research in critical departure from the assumptions characteristic of the institution’s long-ago birth, and some of its still positivist research methods. Thus the museum no longer deals in comparisons between prehistoric and ethnographic “primitives”, and with this same logic, the presentations of the extra-European collections are currently being redeveloped, and will be subject to periodic renewal and deepening.

The collection of Oceanian arts and cultures

“Oceania” is a collective name for the lands of the Pacific Ocean, including the continent of Australia and the island groupings of Polynesia, Micronesia and Melanesia, together numbering in the many thousands. Over recent decades, the Oceanian Arts and Cultures Collections, comprising about 15,000 works, were presented to the public in terms of the following subject areas:

- Houses of men / Houses of spirits (haus tambaran): New Guinea

“Men’s houses” (haus tambaran) are very substantial buildings, up to 15 meters in height and 40 meters in length, traditionally restricted to male adults. These are the places for important ceremonies such as those of initiation, and for sacred objects, including images of ancestors and spirits. The architecture of these buildings reflects the village social organization, with each clan having its own interior space. Men’s houses are still the centers of life in many New Guinean communities, and are considered an important national symbol: the facade of the parliament of Papua New Guinea reflects the form and colours of the men’s house.

- Kula: New Guinea

The inhabitants of the Milne Bay Province of Papua New Guinea are linked in complex systems of ritual exchanges called kula, relying on inter-island navigation in grand outrigger canoes. These wooden ceremonial canoes, up to 12 meters long, have carved and painted end-boards executed by artists of high prestige. The decorations express aesthetic values and hold complex symbolic meanings associated with mythology and s’ ritual.

- Competition for power: Solomon Islands and New Caledonia

In the societies of the Solomon Islands and New Caledonia archipelagos, the most prominent figure is that of the community leader, still a contemporary socio-cultural institution after centuries of history. Traditionally the office was not hereditary, but won through competition based on wealth, prestige and oratorical skill. The encounter with Europeans, which led to the introduction of firearms and new goods of exchange and consumption, profoundly affected the power dynamics within groups and thus the selection of the community leader.

- Ancestor worship (malagan): New Ireland

Ancestor worship is a form of religious expression practiced by certain peoples of Oceania. In the traditions of New Ireland – an island off eastern Papua New Guinea – this worship is particularly elaborated. Periodic cycles of ceremonies (malagan) are held in memory of the deceased, culminating in the performance of masked dancers in front of large sculptures representing ancestor and forest spirits. These festivals are occasions of reverence, rejuvenation and strengthening of kinship ties, and recognition of the prestige and power of the organizing clans.

- Sacredness of power (mana): Polynesia

In Polynesian tradition, the hierarchy of society was strict. The power of the highest class was determined by the divine origin of its members and their holding of mana, or divine power, in particular by the chief. The higher ranks, to avoid the diminishment of mana with the passing of generations, would practice shrewd strategies of marriage. Aristocrats displayed a series of rank insignia, consisting of ornaments, ceremonial objects and tattoos that contained the owner’s life essence and were partakers of their mana.

- The human being and the territory: Australia

According to Indigenous Australians, all living beings are linked to their territory, whose places, such as hills, plains, rocks, river bends, or places of fresh and ocean waters, are the traces of ancestral beings. The spirits of these beings are present in these places, and the individual and their kinship groups thus have deep and essential spiritual bonds with the territory. Humans are united with their lands from birth and forever. This deep and unbreakable bond is represented through bark paintings, masks, painted shields, and body painting. In Australia, European occupation forced the Indigenous peoples to drastically alter their lifestyles, including in relation to their lands. The defense of lands and waters, and the assertion of the relative rights, remains central to their identity.

The Museum of Civilizations is currently reorganizing its presentations of Oceanian materials. New works and archival materials will include some devoted to populations, cultures and arts not formerly considered, along with insights into the provenance of collections in relation to specific historical figures and events.

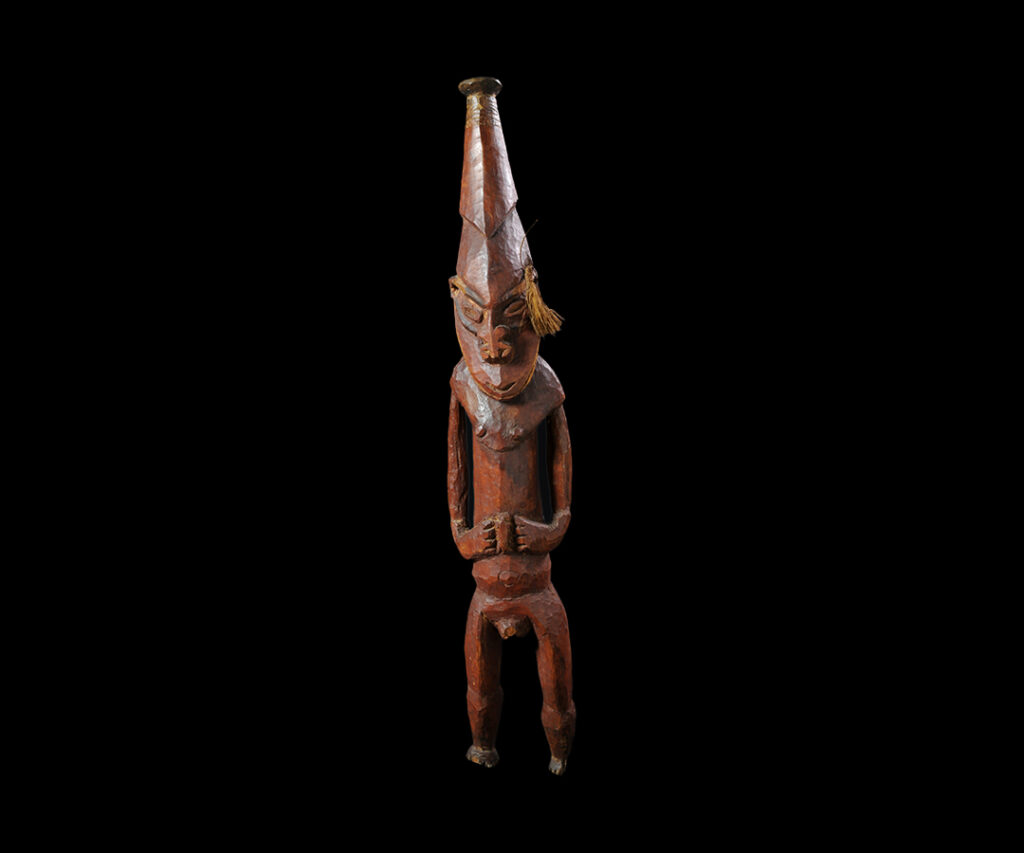

From the collections

The informations contained in the captions are derived from historical documentation or cataloging and inventories that do not necessarily reflect complete or current knowledge on the part of the Museum of Civilizations.

The progressive revision of the collections database is ongoing and will be constantly updated based on the research conducted and by activating comparisons and collaborations with external parties as well, with particular attention to provenance studies.

Archive under updating